Herman Hertzberger, born in Amsterdam in 1932, is one of the world’s pre-eminent architects.

He founded Architectuurstudio HH in 1960 and continues to run this thriving practice in the centre of Amsterdam. Best known for his designs of cultural buildings, housing complexes, offices and schools, he is also a prolific writer and teacher. His books, include a series of Lessons for Students in Architecture and Architecture and Structuralism: The Ordering of Space (2014) and he has held a number of academic posts, including professorships in the Netherlands and beyond.

Herman Hertzberger’s views about how education can be promoted through architecture and how schools should be designed for the young today are the subject of this interview for A&E, as well as his lively insights into his own childhood and schooling in Amsterdam in the 1930s. The interview took place on the 9th of September 2015 at his offices in Amsterdam, with questions from Dominic Cullinan, Dr Catherine Burke and Emma Dyer. A further interview from 2017 is also available on this site, here.

As a small boy I lived in this fantastic urban housing project called Plan Zuid in the South of Amsterdam designed by Hendrik Berlage. It was a special place with good streets and large sidewalks where I could play outside on the street without being run over. I’m convinced that it’s important where you come from, it influenced me very much.

I remember in the neighbourhood there were these sculpted, softly-rounded corner stones at the entrance. I can still remember, something like 78 years later, the feeling of sitting on one. Having a mother who doesn’t say, ‘No, no!’ when you want to explore and to climb over steps, those things are so important for you as a child.

When you design a handrail in the public domain, you must realise that children are going to climb on it. I took a photograph once on holiday: we were just parking the car and we let the children out and the first thing they did was to climb on the handrail. It’s crucial for me for every piece of ironwork I design, I always think ‘What are people going to do with it, apart from just using it as a handrail?’

I remember when I was teaching at Delft (University) and we were designing a school and I asked all people around me, ‘Tell me something about your school life’. First, someone said, ‘There were dark corridors’ and then someone else remembered what their school was like and after a quarter of an hour all these brains were starting to think about their own schools. And then I tried to build a bridge between that (memory) and the designing of a new school. Architects generally have completely left their own experience behind, it seems to be in another part of their brain. But your main inspiration is what happened to you. Hopefully this was a positive experience. If it was only negative, you are not well equipped to be an architect except when you were so conscious of the fact that it was negative that you compensated for that and absorbed all the right things after all. When you’re privileged with a good childhood, you’re better off I think.

Is that is the point of designing a good school?

No, it is not only the point of designing a school, it is the point in general.

What do you understand by education?

Throughout the history of schools, education has always been about how to teach people discipline but for me, education is a wider thing than ‘what you ought to do’ and ‘what you are supposed to know’ but a whole, creative attitude where you go beyond what you ought to do.

I have a Montessori background and the fact is that Montessori is not just about learning to behave. Education is about how to live together, relationships with other people, knowing how to negotiate, how to help people with difficulties, to have a creative approach to everything, so all sorts of things are part of education. Creativity is not just for art – like making paintings – but exploring situations. I have two daughters and they try, I have to be careful with my words here, to ‘educate’ people in art, not just to make paintings, but to explore situations and try to get people to open up, to make them accessible to things that they were closed to. In the Dutch education system there is no time for that. All the time is taken up by the things you ought to know – you are supposed to know the right spelling, the right calculation, only cognitive knowledge. Sitting still and learning things by heart is not wrong, but only part of the story.

What do you remember about your first school?

I remember when I was in the Montessori school as a young child and my father, who was a medical doctor, came to the school. He had been watching me through the window, although I didn’t know and afterwards he said to me, ‘You did NOTHING the whole morning!’ I didn’t know what to say at that time. But now I know exactly that I should have said ‘I was working on my network.’ All morning I was going from place to place and talking to people which is, of course, very important after all.

I had so much freedom in that school. In my second year I made a project about tramways. It came to me out of the blue. I even went by tram to the end of every line to see what was there and made it into real project with drawings and everything. And the teacher let me do it. I spent something like half a year on that. Nobody realised that this would be the work I am doing the rest of my life: although not with tramways, but with buildings, it’s the same idea.

I remember asking the teacher where to find something and she said ‘Go to the cupboard on your right.’ And I didn’t know which was right or left but I did know that you eat with your right hand. So I remember myself standing there imagining eating in the wrong hand and thinking, ‘No, no this is the right’. So this instruction by the teacher was the right thing.

Did you go to several schools when you were a child?

No, just one.

And you started at the age of six?

Four, I think.

Do you remember the school building?

Of course, I could draw it. It is in one of my books, Space and Learning.

This school was fantastic. There were big classrooms with what we called ‘the kitchen’ which was a place where you could splash water. And there was ‘a quiet room’ where you could rest, a place with benches and a curtain, where you could go when you wanted to concentrate and you could close the curtain. This space was also used for preparing a play for the whole class or for a group.

Did you have special places in the school where you liked to be?

Yes, I could talk for hours about this. Especially the higher grade classrooms where you were supposed to be the next year. Only the corridors were no-go areas. That’s where the coats were hanging. And I remember, one of those classic things, when I did behave so badly that the teacher sent me to the corridor. I remember standing in the corridor with nothing to do, standing with the coats, in this place with no real windows and trying to find something to eat in the pockets of the coats.

Do you think that the Montessori experience was influential in later life?

Oh absolutely. It was crucial to my whole development. One very important feature of the Montessori school is that everything is openly displayed and available so that you can be inspired by what is there. The teacher says to you, ‘So, what are you going to do this morning?’ ‘I don’t know’. ‘Well, come back after ten minutes and tell me. And then you look around, thinking ‘Is this something for me, is that something for me?’ Do I want that? And you choose something and you are inspired. And that became the inspiration for how I make suggestions to the school users in my practice.

So this Montessori education influenced your work in general, not just the school buildings you design?

Yes, in general. This led to my main idea of keeping things open for people, i.e. leaving room, and beginning projects with discussion rather than choosing to define everything to the last detail.

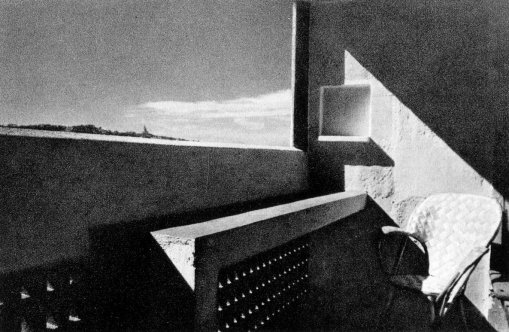

My ‘teacher’, and the ‘teacher’ of most other architects today, is Le Corbusier, who did things like making a small niche in the wall. If you have that niche in your house made of concrete, you cannot take it away and you are invited to do something with it. Of course you can cover it – I’m not a psychiatrist but it might be possible that some people would do that. Others might put something in it, like a plant. So in effect, the space or the features of the space are challenging you, asking you an answer.

Without suggesting anything specific?

Without suggesting in a specific way. It’s just saying ‘Do something with me!’

How does that relate to your designs?

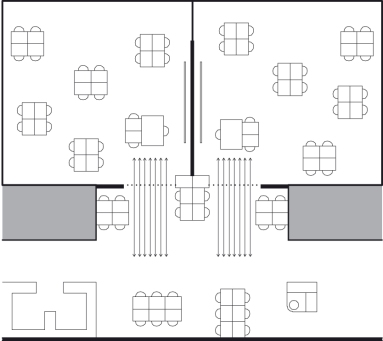

When you do something different, the mistake most people make is that they think that they have to get rid of the previous paradigm. That you should not do. I mean, you need classrooms but only sometimes. There are situations when it’s very important that the teacher explains something to everyone. But there’s a lot of work you can do yourself, or with just a couple of others.

How about the classrooms?

So, in my architecture I did not want to deny the classroom, but to put it in perspective. This is what happened in the United States in the fifties, they made really big rooms and people were sitting there and it became a mess, because they were distracting each other. Distraction can be fruitful but it can also be disturbing. The point is, how can you make it fruitful and not disturbing? Therefore the idea of articulation is very important. The space should be articulated in the sense that you are sort of protected, but feel part of each other. It’s a sort of balance between concentration on what you are doing and being part of the whole.

Some school designers in England, in Hertfordshire in the 1950s, ‘60s and ‘70s, also designed articulated spaces with small bays. But perhaps you think they suggested too much?

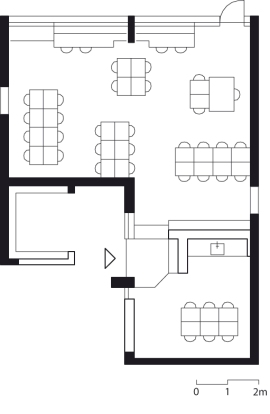

I’m not saying they were wrong, it was a good development. But I think you can take some further steps and instead of corridors you could make what I call a ‘learning street’. The Dutch regulations want to make the school corridor very broad. Because when people have to sit still for two or three hours, as soon as the bell rings they explode in movement because they had to sit still for so long. You don’t need large corridors for that reason anymore, but you can make nooks and places for people to sit and have tables there so that you get a ‘learning street’, like a shopping street.

When you were studying architecture in Delft, did you plan a school?

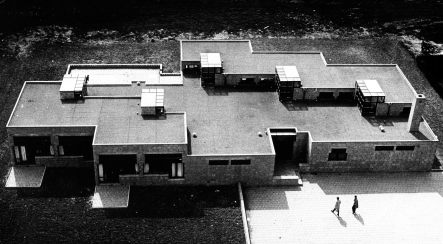

No, at that moment I was not looking at schools: I didn’t design any schools during my training. But my wife was a kindergarten teacher and when I had just finished my studies her school asked me to design a new building for them. And since Delft is a university town, there were lots of connections behind the scenes and I later heard that all these professors had called each other and asked ‘Can we trust that guy?’ It seems that the information about me was alright and I was allowed to build that school and that was the starting point for me. And that school in Delft is still not outdated.

How did you develop your ideas about school design in that first school?

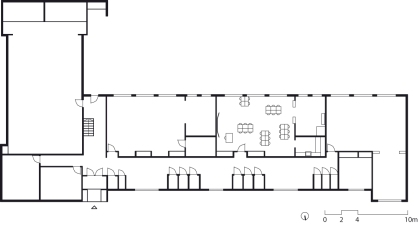

I thought it would be a good idea to have an area at the back of the classroom where you are more secluded and then gradually moving to the outside to correspond with the type of work that you’re doing. So when you’re doing work that makes concentration easy, like clay, painting etc., you are closer to the outside, and when you have to do mathematics and difficult things like that, you are closer to the back of the classroom. So the classroom was articulated in three zones. And there were niches for the coats and cloakroom, but instead of a corridor there was a central space for everything communal.

When I visit that school now, so many years after it was designed (in 1960), you can see in that central space all sorts of special projects like a bee project and they have the Montessori ‘cosmic education’ where they hang the sun and moon and the earth and planets at the end of the corridor and people can see their relative size and the distance between them. Everyone can take part.

So that school today is still just as you intended?

Yes.

Is that true of all the schools you have designed?

Even if they have changed, the main concept is still clear.

Do you ever consult the pupils about the designs for their schools?

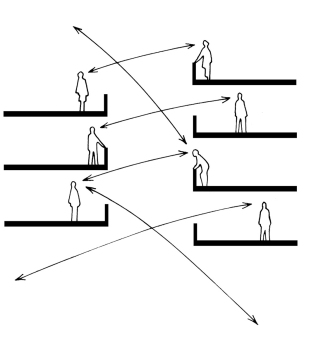

Sometimes the teachers have good ideas. Sometimes they have no ideas. At the beginning when I still had to consult the Ministry of Education they would say ‘Hmm, stairs, we cannot have that because the children will fall down on them’. And I thought ‘What can I do?’ and there was fighting and arguing. And eventually, the man from the Ministry said ‘When the teachers accept it, I’ll accept it’. Then I talked with the teachers and I had the same discussion and they said the same thing, ‘But the children might fall.’ But then one or two teachers said ‘The children are more stable than we are!’ And in the end the balance tipped. So you have to fight to begin with but then after that, nobody ever mentions it again. Although in one of my last schools I made a set of steps and I got a furious letter from one of the parents saying ‘These stairs are impossible, how could you ever make such a stupid thing?’ But this was a world of steps, and nobody ever falls down. Children are very clever. But this parent could only see this set of stairs as a way to go up or to go down; she didn’t see that that was only one of its functions.

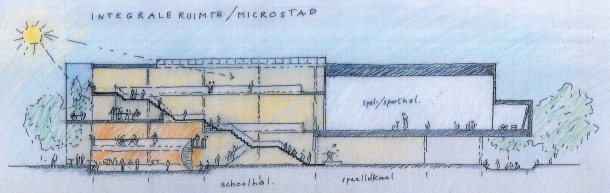

I think a school should be like a small city. In a city you have small places, large places, all sorts of secluded and semi-secluded places, you have vistas and you have all sorts of activities. In effect, these pupils are not yet of an age to go into the city and explore the life of the city but they should explore life through the school, so you must create as many conditions as possible in the school so that they experience the world through the school building.

Is it still possible to make schools with these big staircases in this way in the Netherlands?

At the moment we are designing a school, which has a long line of stairs going up and up to create a stepped street. So the answer is yes, you can, except that the budgets are awfully small but in this case the price is OK for them so they will build it.

The problem with school budgets is that the budget covers the whole programme and the programme defines all things: so many square metres for library; so many square metres for the director; and for the secretary. It’s all precise and then they take a percentage, which is either 10 percent or 8 percent when they want to earn money for ‘overhead space’ (the float). So for all the unofficial things you want to do, you have to steal from this overhead space. When I see a programme, I can tell you in five minutes whether it is possible to work with it or not. Everything is dependent on that percentage (given to overhead space).

When the teachers say that their classroom has to be 50 square metres, don’t try to make it 49, because they will say, ‘I have a right to have 50, give me one more! So what I do is to make a zone which is difficult to tell whether it belongs to the classroom or not, so it has a sort of double use. And I say to the teacher, ‘Here is your 50 square metres’. And the teacher says ‘Yes, but I want my doors here.’ And I say, ‘Yes, you get your doors here but if you open your doors you have this extra space, and you will have more than 50 square metres with this. If you agree with my plan, then you will have 54 square metres’ and they say, ‘Yes that’s a good thing, that’s a deal!’ This is how I work with teachers. You have to be really convinced of what you’re doing, you have to fight for that and sometimes you don’t win, but sometimes you do.

Do you ever look at what other school designers have created?

No. I’m a supporter of modern architecture, but the strange thing is that there are few schools from the modern movement. They made large villas, some community buildings but no schools. It’s very strange. Actually there are something like five or six famous modernist schools. Richard Neutra made one in California. And there is the famous design by Hannes Meyer in Basle, but it was never realised and besides, he was not concerned with all the things we have been talking about, he was concerned with the right quality of air and of light: in fact he was starting to make the rules for minimalism. And of course we have the open air schools of Duiker in Amsterdam and in Suresnes, Paris by Baudoin and Lods.

Which other schools are worth knowing about?

Aldo van Eyck made two similar schools which were very inspiring if only in the formal sense..

Can you think of anything that a teacher said to you that changed the way you thought about school design?

I cannot say one particular thing, but you have to be open. I am 83 now but I actually still believe in learning and change and not holding onto my old standpoints. At this very moment we are working on a plan to re-make the Centraal Beheer office building, which is unoccupied, for student accommodation. People don’t need office buildings anymore, there are still office buildings, but most of the work is done at home or in coffee corners.

You were the original designer of this building.

Yes. This is the proof of the pudding, whether your spaces are made in such a way that you can also make say a hospital out of a school. Because the principles we are talking about have a universal value: articulation; making places; creating a view; protection; basic things. We just finished a big university building that is almost without corridors with a lot of voids. But in a secondary school in Amsterdam by means of a sort of split level all of the floors are in contact with each other.

The design of this school had some problems with the fire department but by making balconies so that people could always escape from the outside it was accepted. It would be even more difficult to build that school today because the fire department would force you to use very expensive glass today.

What’s happening today is that architects are just at the surface of each programme and there are all sorts of managers that make the programmes more complex with energy and climate requirements and increasingly safety measurements. They hire management institutions to make the programme and the architect is supposed to be just there to execute it. It is really hard when you’re building a school to get in touch with the director or head teacher, let alone the teachers or the pupils or students, there’s a large distance.

Architects today are supposed to be completely sure about everything and yet you are not. But you have to pretend you are. And sometimes things go wrong.

You have to make friends of people who believe in you.

It’s a power play.

What about other pressures, like the emphasis on sustainability or the materials that you use?

It’s not a problem to make things sustainable. I’m not against that. The only problem is that a lot of your budget is absorbed by all of those things. I’m not saying it is unimportant though.

David Medd, the architect who designed schools in England in the 1950s, ‘60s and ‘70s’, talked about a ‘built in variety’ in the spaces of schools. He always said ‘You start with the activity, then you think about the furniture, the interior decoration and arrangements and then you think about the building’.

I disagree. I don’t think you can ‘build in’ variety. Variety must come from people themselves. I don’t use too many colours in schools but I’m happy when they say ‘Oh it’s too grey, we want to make that red’. I’m not going to choose the colours for them. As an architect you must make the conditions and the potential for variety and that must come. But I’m not purposely making differences because of this idea in psychology that people like variety. You must build in the possibilities for it, but there must also be a structure and a clarity that keeps the whole thing together.

I like to design columns and if the school is going to paint one red and one blue, that’s not my problem. But I think the structure of the whole thing should have some sort of clarity. You have the rules of the game and then the game itself. In football you have specific rules: you cannot do this or that; you have to remain within the lines otherwise the ball is out or offside. These are the rules and the rules are not restricting the freedom of people but stimulating their freedom because the freedom is about what people do within these lines. I could also choose chess as an example: what you can do with all the chessmen is quite limited, but a player chooses what they can do within these rules’.

It is freedom, but the designs you offer suggest certain sorts of activities. The stairs you design are not just stairs, but places you can lie on, or draw there. So it’s not a total freedom but an allowance.

Yes, allowance.

And an encouragement to work in a certain way, even?

Yes, sure.

If teachers understand that then it allows them to work in a certain way too?

As long as the teachers leave some freedom to the students, then the students might do it.

They might. I don’t know how it is in the Netherlands but in England there is less and less freedom and much more control over every moment of time.

Yes, that’s the case everywhere. There is a certain level of what is asked by society, asked by the market and the big companies and since all want to have a good position it needs to be followed to a certain extent.

What are you proudest about in the field of school design, what is your legacy?

Pass! (he laughs).

Is there anything particularly that you feel will last?

Well, a lot of things. One of the characteristic things in many of my schools, although not all, is the idea of having big stairs which are not just to get up and down but which are tools for working. Like in the Apollo schools, you can see people are working on those stairs: they are using the stairs as tables. They even take off their shoes because they have the feeling of sitting on a table. When I was designing these stairs I was talking about an amphitheatre and people in the office said that I should make it them in marble, but I said no, that it would be too cold. And they said ‘yes, but then it’s not an amphitheatre!’ We had that sort of discussion.

Is the quality of wood for those stairs important?

No.

So they could be plywood?

They are plywood. The quality might not be enduring, but it’s not about the quality of the wood in first place, but feeling that wood is something else other than, for example, plastic is important.

If the school is supposed to be a city, it’s very important where the light comes from, from the side or from above. In the streets, the light comes from above and it’s a specific condition. The quality of the space is very much dependent on the acoustics too, don’t forget about the acoustics. Many people make fantastic spaces but you can’t live in them because the acoustics don’t work. So you have to have the right amount of sound absorbency. So you must be a little bit professional and not just an artist. To be a good professional architect you must know about these things. What you put on the floor is also very important, so for me the materials are not just a matter of aesthetics but must support the idea. A sense of aesthetics will be of second nature to you but that’s very personal, very difficult to talk about.

My designs have a lot to do with empathy, the fact that you are putting yourself in the place of the people that use it. Too many architects are busy with the structure of buildings but not with the people. I see that all the time. So most of the time architects don’t think about how people feel in their buildings.

Are there any architects working today who you admire?

There are some, like Marlies Rohmer. But if you ask me to mention one architect who really influenced me, it is Scharoun. I learned very much from Scharoun, he was very good, except for the fact that I believe in right angles and straight lines. Gravity is straight, is vertical and the horizon is horizontal.

Rudolph Steiner wanted no corners, no right angles.

Scharoun was following Steiner but he made very beautiful schools.

So Rudolph Steiner was wrong?

Yes, he was absolutely wrong but, as far as architecture was concerned, he was wrong in a nice way.

All images kindly provided by Herman Hertzberger, ©HH.

Another interview with Herman Hertzberger from 2017 is also available on this site, here.

Wow, such a great interview, thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person