The design of spaces in schools for therapeutic purposes is the focus of this series of posts. These are spaces in which children can safely identify and express difficult or complex feelings with a trusted adult. Sometimes these spaces are needed by children in a crisis and at other times they are the setting for regular, planned sessions for counselling or emotion coaching*, in which their understanding about their own emotions are developed through their relationship with a key adult. Some schools already have rooms designated for therapy and counselling while others have adapted cupboards, libraries or corridors for this purpose. Of the many schools that I’ve visited, I haven’t come across a single one that doesn’t have a need for such a space or that doesn’t try to address this need in some way.

Running through all of these posts is the contention that these spaces should be considered as essential in supporting the mental health and well-being of our children in educational settings and that they should be designed into new schools and created or refurbished in existing schools to address this need. Therapeutic spaces in schools are rarely discussed so my aim here is to bring to light significant elements and qualities of these spaces and offer suggestions for how to create them so that children’s emotional needs can be successfully supported in schools.

In this introductory post, I briefly define what is (and what isn’t) a therapeutic space; I talk about why these spaces are needed in schools and offer a theoretical perspective (attachment theory) that provides the basis for a rapidly growing number of schools’ understanding of pupils’ emotional needs. In my second post, I outline four principles that need to be established for these spaces to work successfully; in post three, I consider how the qualities of safety, security and stability (Bomber, 2011, p.33)** might be communicated to children in these spaces and in post four, I look at other, different types of spaces, such as ‘nurture rooms’ and ‘sensory rooms’ where children might go for support with their emotional, social and sensory needs and at the bigger picture of design for these spaces. I will also offer an annotated bibliography of references and resources that I hope will be of use to architects and designers, teaching staff and therapists working in schools.

At its best, design disrupts the taken-for-granted, the normalised and the neutral and it is for this reason that I’ve chosen to consider the therapeutic rooms from a design perspective, while giving contextual information when needed about why they are essential. Some of the ideas discussed in posts three and four about ideal qualities of therapeutic spaces and how to set up a therapeutic room from scratch might appear simply to be common sense. However, as someone who taught in several schools and visited dozens of others, I am aware of the ongoing, everyday pressures of teaching and the difficulty of making time and taking responsibility to change spaces, as well assimilating ever-evolving good practice and content changes to schemes of work.

Beyond the expectation that therapeutic spaces for children should be available in all schools, I will also reflect upon how therapeutic spaces are currently used, drawing on the experiences of those who currently use them. Some of these insights have emerged from a research study in primary schools that I lead with educational psychologist Sara Freitag, located in four primary and infant schools to the west of London. These four schools demonstrate excellent practice in this area. We are planning to extend this study to include secondary schools in the UK but currently the emphasis on this research is primary-specific.

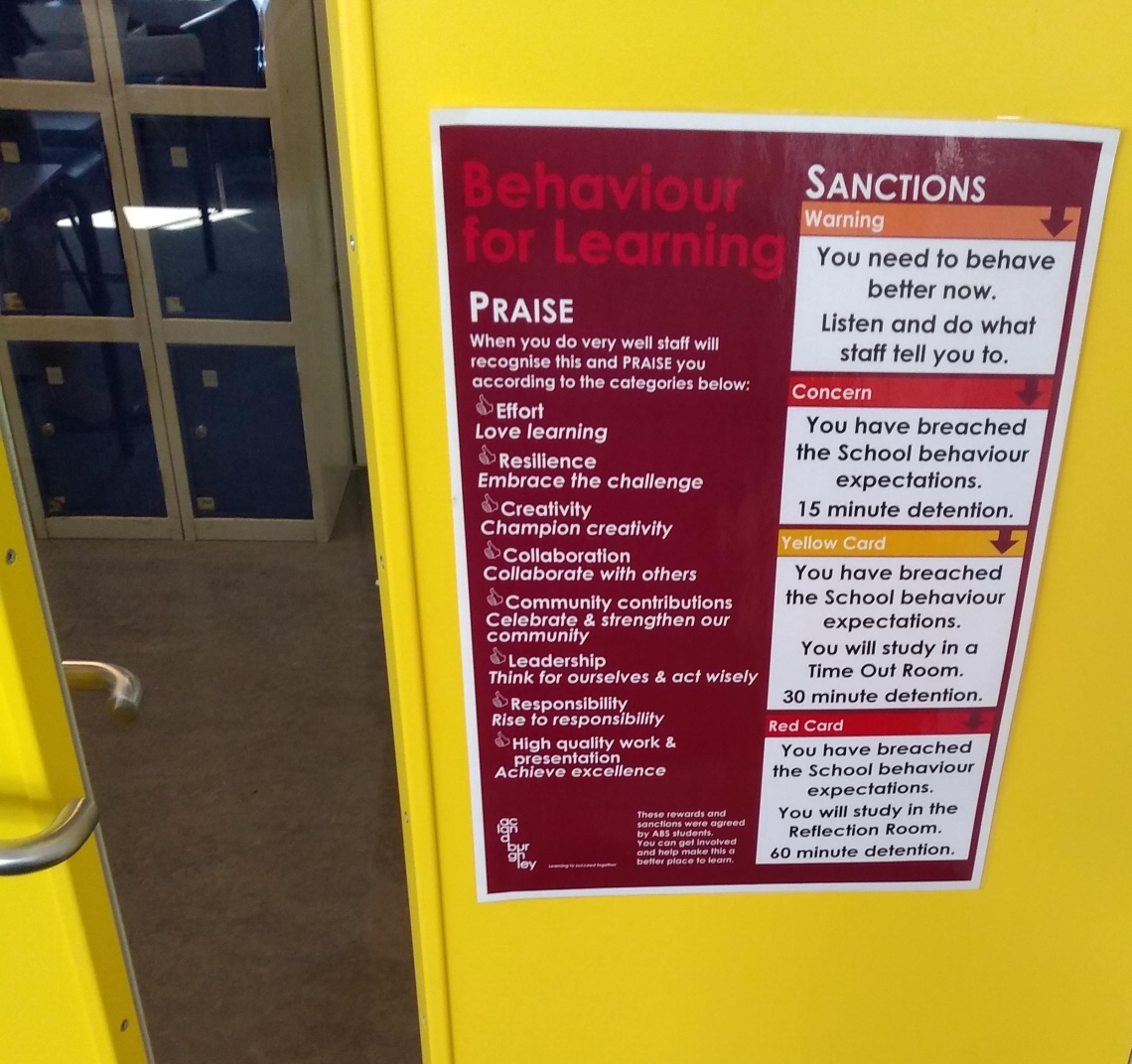

First, a definition. The purpose of the type of space that I discuss here is essentially for therapy and counselling: an enclosed room or partitioned area in which a trusted adult offers emotional support rather than support with learning. They are not isolation rooms or the Orwellian-named internal inclusion units that exist for the purpose of creating short term exclusions inside a school, without the need to follow a formal external exclusion procedure, a procedure that brings consequences for school statistics and an administrative burden. These are spaces in which students are separated from their peers and follow a rigorous timetable with prescribed, supervised breaks and toilet visits***. These rooms have featured in the UK national press in the early months of 2020.

Therapeutic spaces are the antithesis of isolation rooms, offering a safe haven to return to when needed, somewhere a trusted adult or mentor will listen, comfort and support. It may be a space where regular sessions take place or somewhere away from the public gaze to take a child who is very distressed and who, as one teacher told me, ‘just needs to get it all out and be able to cry in a safe space where they know people aren’t looking, (especially) if they don’t want people to find out.

Children in therapeutic spaces are offered freedom of access and the choice to leave whereas often the children who are sent to isolation rooms, which they can’t choose to leave, are the ones who would benefit the most from a safe space and a listening ear. These are students who may have experienced very difficult situations in their early lives and who sometimes communicate their feelings through anger and frustration to try to get the attention of adults in the school who they hope might be able to help them. Whether they are sent to a therapeutic space or an isolation room or go to a therapeutic space is likely to depend upon whether the school is able to offer the former or confine them to the latter.

Children who have experienced neglect, loss, separation, violence, abuse and bereavement in their formative years, perhaps even while they were still babies, can find it difficult to form trusting relationships with adults around them, even if their situation has now changed. This leaves them feeling constantly unsafe. Their early experiences have taught them that adults are not to be trusted. Educational psychologists working with schools advise teaching staff to recognise that challenging behaviour in class may be a sign that the child is feeling overwhelmingly unsafe and at risk. In the three local boroughs where I work as an advisor to schools and families with children previously looked-after, attachment theory is a lens through which educational psychologists look at difficult and damaged relationships and expressions of distress by children. Attachment theory was first proposed by John Bowlby (1907-90) and is concerned with how human beings unconsciously adopt self-protective strategies within relationships at times of perceived threat. Our attachment system enables us to maximise the availability of comfort, safety, proximity and predictability (Guthrie, 2019). Attachment theory seeks to explain the influence of very early relationships upon the later behaviours and underpins these posts here too, principally through an understanding that challenging behaviour in schools signals that something needs to change for the child and that they need more support, not less.

The people working in schools that I mention across this series of posts have all set up their own therapeutic spaces. They come from a variety of different backgrounds and their previous roles include teaching assistant, assistant headteacher and counsellors. They are all professionally trained in supporting children’s emotional needs as well as in safeguarding. I have changed their names and have not identified their schools but am grateful to them all for their insights and inspired by their commitment to and passion for their work.

In my next post, I propose four principles to support a successful therapeutic space in schools.

Notes

*Emotion coaching helps children (and adults) to recognise the range of emotions they experience, why these emotions appear and how to cope with them.

**Bomber, L.M. (2011). What about me?: inclusive strategies to support pupils with attachment difficulties make it through the school day. Duffield: Worth Publishing.

***IC Free is an activist group set up by young people, protesting against exclusions and isolation units.

Your fascinating blog reminds me that when I started designing schools as an ILEA architect in 1969 people talked about providing a ‘kiva’… a word I’d forgotten for half a century; did that come from the Medds? And did it vanish…?

LikeLike

Yes it did! Do you know of Catherine Burke’s work? She has documented the Medds extensively and writes about the kiva at Evelyn Lowe school in Southwark (I think). Have you ever written about your experiences of designing schools in the 1960s? I’d love to hear more.

LikeLike

Your fascinating post reminds me that when I started designing schools as an ILEA architect in 1969, people talked of providing a ‘kiva’ – a word I’d forgotten for half a century till today. Did that come from the Medds? And did it vanish as fast as it appeared?

LikeLike