Film review by Emma Dyer

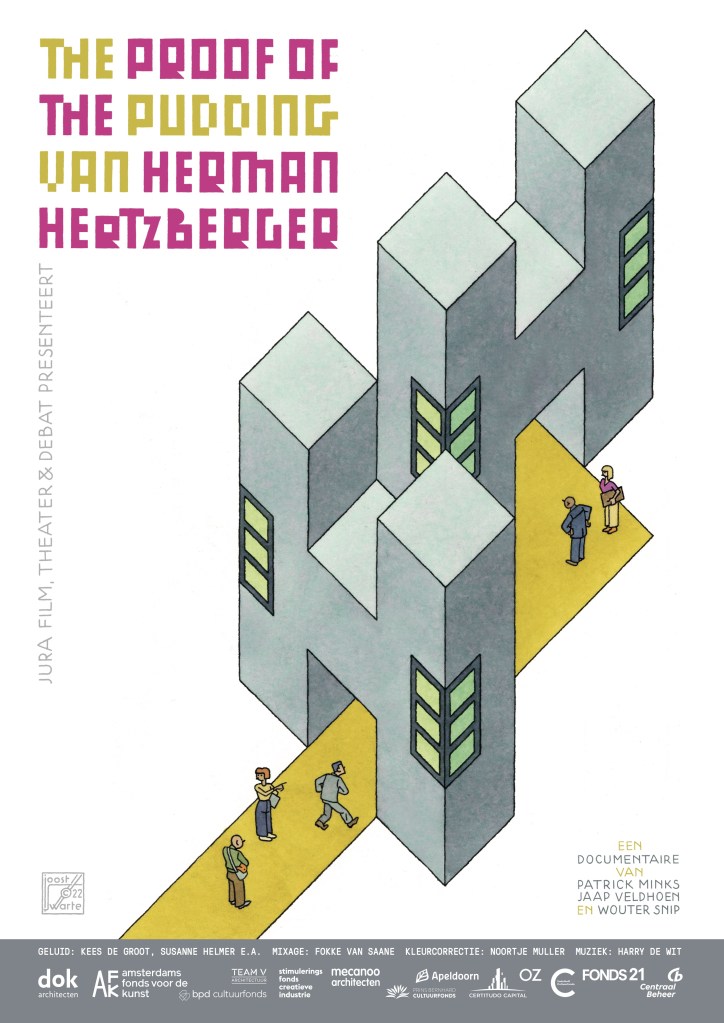

The Proof of the Pudding is an affectionate portrait of the architect Herman Hertzberger by filmmakers Patrick Minks, Jaap Veldhoen and Wouter Snip. Through a series of interviews with Hertzberger, his colleagues, and some of the people who have a personal experience and appreciation of the design of his buildings, the film builds up a portrait of the architect who is now in his nineties. It’s a special experience to watch Hertzberger still at work at his vocation, using his life’s experience to communicate his passion for his work and his commitment to curiosity and learning.

The film’s narrative follows an attempt by Hertzberger’s architecture firm AHH, now led by his successor Laurens Jan ten Kate, to repurpose the celebrated office building Centraal Beheer, Apeldoorn (1972) for housing. It is a familiar scenario for our times: the building had fallen into disrepair after the owners went bankrupt, followed closely by the failure of the bank that then owned it in the noughties. When Certidudo, the property developer, bought the ex-insurance company’s building for a pittance, they persuaded AHH to be involved in the remodelling. In Hertzberger’s own words, ‘the proof of the pudding’ (from which the film’s title is taken) lies in his own hope and desire to restore the building: ‘And when that empty shell, as it has become, can be turned into dwellings, then I think I have proved something.’

Throughout the film, seemingly insurmountable obstacles emerge, from ‘the worst kind of asbestos’ in the windows to a second architectural firm being brought in to lead the project. Although there is a less than hopeful ending to the film, it is a delight to watch Hertzberger still insightful, still eager to work, still curious, and appreciative of the work of his predecessors and followers.

While the dramas of the redesign project are threaded through the length of The Proof of the Pudding, so are merry interviews with ex-workers from Central Baheer and black and white photos of the flamboyantly decorated workspace (fish, turtles, chianti bottles and nets) where fun was undoubtedly the order of the day. These contribute to the generally joyful rather than wistful tone of the film. Hertzberger’s intention to build places where people ‘can feel at home and safe and where people can have contact with each other’ was realised in these offices, with the closeness between upper and lower floors and diagonal sightlines. Unsurprisingly, the building’s ex-employees remember their worklife with fondness and one of them is interviewed saying that they would happily live there if they could.

A second thread running through The Proof of the Pudding charts Hertzberger’s extraordinarily successful career as an architect from its inception in his childhood home in Amsterdam. The filmmakers capture him caressing the concrete globular shapes that decorate the exterior wall of his childhood apartment and his appreciation for architecture that ‘isn’t aloof.’ Hertzberger also muses about the small panes of glass in the front door having certainly saved lives by providing a peephole to warn of approaching Nazi officers and he reflects that had the war continued for six months longer, his Jewish father and family would certainly have been taken by them.

Hertzberger is lively and adaptable, blurting out that a statue of him (as it is unveiled) doesn’t resemble him in the slightest but then giving a graceful speech to smooth things over. He is robust enough to emerge from a ravine in the remote French countryside into which he has fallen, escaping with just a few scratches. And he characteristically balances the theoretical and the practical when talking about architecture made by himself and others, adamant that no ideas belong to any one person: ‘Learning is always the most important thing. You can be proud of having a discovery but don’t think it is your private discovery, it is always what you assembled from what you learn from others.’

In philosophical mode, Hertzberger is pragmatic about beauty saying, ‘Well, beauty is not really my thing, no. It’s all about the meaning, about the value of things. I think beauty is a difficult idea.’ Meanwhile, the filmmakers focus tenderly on some of the pleasing objects on his shelves and soon Hertzberger himself has fixed on a tiny model of a chair that someone has made for him, saying: ‘I think it’s a great design. I think it’s much more beautiful than the famous chair by Rietveld. Yes, this is a real miracle.’

Hertzberger demonstrates how the gaps he leaves in his designs for people and things open themselves up for beautiful things to happen. We are taken inside one of his Apollo schools (1983), complete with students, to appreciate the little nooks and child-height shelves and then the steel staircase that emerges from the concrete flight of stairs. As architectural historian Hans Iberlings remarks, ‘There is an awful lot of energy and attention in those stairs: a crucial element in this architecture, how you negotiate the building.’ This wouldn’t be a film about Hertzberger without the nooks and stairs and his energy to create a freedom in the design.

Hertzberger has been a prolific author and has written about and diagramed many of his designs in his books so many of the explanations he gives won’t be new to his admirers and students. But it is a pleasure to hear him talking about his ideas in situ and to see him working at his desk on his designs. We witness his contentment in being valued but he is also clear-eyed about the tensions between the architectural refurbishment and a company like the developers who must be dealt with:

‘My vision as an architect conflicts with how people think about profitability. Aldo Van Eyck said that architecture should be brought in like contraband. And that is ultimately where problems start. A property developer like that also has fixed schedules. It has to fit in with those schedules. These are things. They are determined. And I have, of course, spent my life trying to create space where other things are possible. The space where new things are created, which are open. That’s the motto of this profession for me.’

The Proof of the Pudding is unusual in giving a revered, working architect the time and space to reflect on his previous work at length and on what he might still hope to create in future, even at ninety. A vein of deep appreciation for what he has achieved and for the curiosity and doggedness of the man runs through the film. The Proof of the Pudding is highly recommended for anyone who admires Hertzberger’s work or seeks an introduction to it and those with an interest in education and architecture may also particularly value the opportunity to see inside an Apollo school as it is currently being used.

The proof of the pudding is in Dutch with English subtitles, running time 1 hour and 40 minutes.

stichtingjura.org/the-proof-of-the-pudding

(Trailer in English)

primevideo.com/detail/The-Proof-of-the-Pudding-van-Herman-Hertzberger

(Full film available on Prime Video only in the Netherlands)

1 Comment